Health, Wellness & Spa

Mayo Clinic discovery reveals how lungs repair themselves, opening doors for regenerative therapies

Mayo Clinic researchers have identified a molecular “switch” that helps lung cells decide whether to repair damaged tissue or focus on fighting infection — a breakthrough that could pave the way for new regenerative treatments for chronic lung diseases.

The study, published in Nature Communications, sheds new light on how specialized lung cells balance repair and defense, and why this balance often breaks down in conditions such as pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and severe viral infections, including COVID-19.

“We were surprised to find that these specialized cells cannot do both jobs at once,” said Douglas Brownfield, PhD, senior author of the study. “Some commit to rebuilding, while others focus on defense. That division of labor is essential. By uncovering the switch that controls it, we can start thinking about how to restore balance when it breaks down in disease.”

How lung cells choose between repair and defense

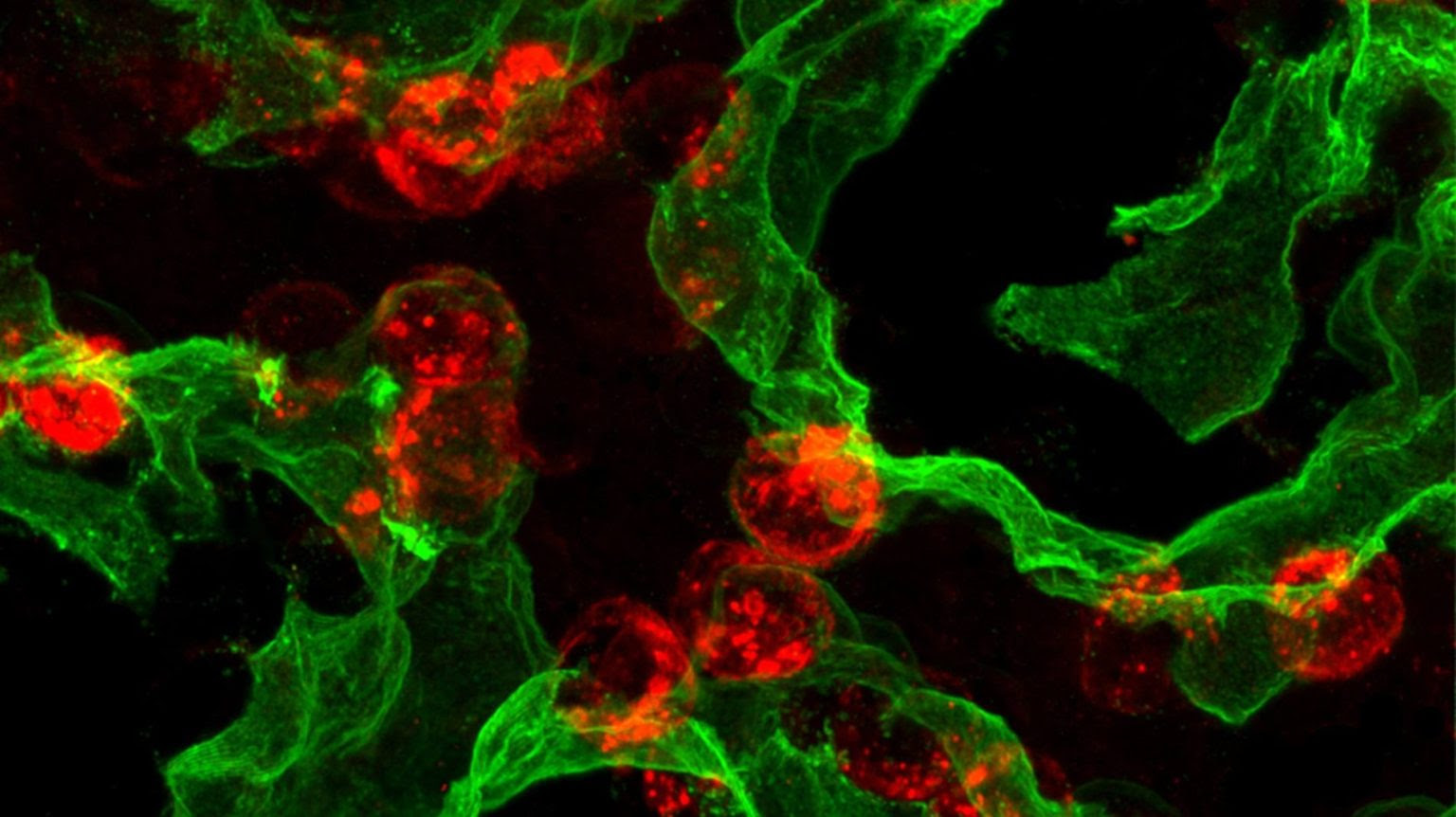

The research focuses on alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells — critical cells that protect the lungs while also serving as backup stem cells. AT2 cells produce proteins that keep the lungs’ air sacs open, but they can also regenerate alveolar type 1 (AT1) cells, which form the thin surface required for oxygen exchange.

While scientists have long known that AT2 cells often fail to regenerate effectively in chronic lung disease, the reason behind this loss of regenerative capacity remained unclear.

Using advanced single-cell sequencing, imaging techniques and preclinical injury models, the research team traced the developmental “life history” of AT2 cells. They discovered that newly formed AT2 cells remain flexible for about one to two weeks after birth before becoming locked into their specialized role.

This process is governed by a molecular circuit involving three regulators: PRC2, C/EBPα and DLK1. The researchers found that C/EBPα acts as a molecular clamp, suppressing stem cell activity. For adult lungs to repair themselves after injury, AT2 cells must release this clamp to regain their regenerative function.

Crucially, the same molecular switch also determines whether AT2 cells prioritize tissue repair or immune defense — helping explain why infections can slow or derail lung recovery.

“When we think about lung repair, it’s not just about turning things on,” Dr. Brownfield said. “It’s about removing the clamps that normally keep these cells from acting like stem cells. We discovered one of those clamps and how it times the ability of these cells to repair.”

Implications for regenerative medicine

The findings highlight promising new targets for regenerative therapies. Drugs designed to adjust regulators such as C/EBPα could help stimulate lung repair, reduce scarring in pulmonary fibrosis, or improve recovery after severe infections.

“This research brings us closer to being able to boost the lung’s natural repair mechanisms,” Dr. Brownfield said. “That offers hope for preventing or reversing conditions where, today, we can only slow disease progression.”

The discovery could also support earlier diagnosis by helping clinicians identify when AT2 cells are stuck in a single state and unable to regenerate. This insight may lead to new biomarkers for lung disease and aligns with Mayo Clinic’s Precure initiative, which focuses on detecting disease at its earliest stages.

At the same time, the work advances Mayo Clinic’s Genesis initiative, aimed at preventing organ failure and restoring function through regenerative medicine. Researchers are now testing strategies to remove the molecular clamp in human AT2 cells, expand them in the lab and explore their potential use in future cell replacement therapies.